SHIPS AND US

Ships, sailors and their voyages have played a critical role in the development of mankind. Battles between ships and naval fleets have shaped the course of history for just as long. And despite millions of shipwrecks, world commerce continues to be influenced by the ability of ships to transport goods and people from one corner of the world to another.

Through the ages, countries, syndicates, individual ship owners, captains and crews, have amassed fortunes from lucrative voyages. Almost constantly, advances made by science, industry, and the discoveries by tenacious explorers, were all accompanied by ‘the ship’. In terms of man’s development, maritime innovation has been a key factor.

Ships and shipping might just seem to be another form of commercial travel, and fraught with the dangers and casualties one might expect, but shipping regulations were at first non-existent. Naval regulation came first, followed by private ship owners, who were slow to risk profit margins. Poor regulations were probably responsible for the loss of thousands of vessels, their crews and passengers, goods and riches which lie scattered on the seabed.

Navigation instrument Astrolobe, from 1588 Spanish Armada wreck, Irish coast

THE INTRIGUE OF SHIPWRECK

What has endured, are the tales and folklore of ships and shipwreck, stories that have grown and reached millions through literature and the cinema. It is difficult to attribute only a single reason why the colourful swashbuckling stories from the 18th and 19th centuries continue to excite. In particular, are the stories surrounding the activities of pirates, corsairs and buccaneers from around the world. Ireland figures prominently in this regard, with its own stories of privateering and pirating from around its coast. One of its best known ‘pirates’, one of only a handful of women who embraced this dangerous career, was Grace O’Granuaille from the coast of Mayo. The story of the privateer Fame 1780c and the 17th century Ouzel Galley being just two more of the many.

Why accounts of the final moments of a vessel being dashed onto the rocks, sometimes within yards of land and refuge, and the desperate efforts by crew and passengers to escape their fate, continues to excite the imagination in the way that they do, remains complicated.

DIVERS, WRECKS AND DREAMS

Since ships went down, man has dived to save them or to save what was in them. The history of diving is a subject involving various sciences and has been addressed comprehensively through the ages by ‘philosophers’, academics, and amateurs alike.

It might appear that there are few incidents of consequence concerning diving and salvage that took place in Irish waters. This is of course not the case. One can immediately point to some of the interesting salvage/ investigations performed by the Royal Navy in Irish waters during both world wars. Amongst them, been operations on sunken submarines and the retrieval of precious metals from wrecked merchant ships. The diving operations on the controversial Lusitania and the epic retrieval of gold bullion by commander Damant out of the liner Laurentic being just two cases in point. These are among many stories told on the shoulders of herculean feats, such as the scrapping of the surrendered German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow after WW1.

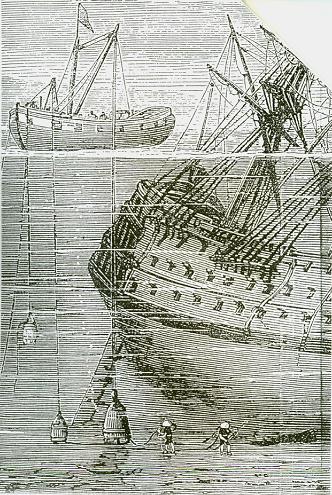

These aside, there are also some interesting examples of earlier diving operations around the coast of Ireland, some successfully retrieving silver and gold treasure from foreign vessels, such as those by Jacob the Diver at the turn of the 16th century. Prominent amongst them,, and with some mystery surrounding any success, a most interesting example occurred in June 1783. Having wrecked the previous March, attempts were made to recover a large amount of silver from the wreck of the Imperial East Indiaman, Comte De Belgioioso. Bound for China, she was said to be, ‘one of the richest ships ever sailed from Liverpool’. This particular story contains all the juicy ingredients; adventure, sunken treasure, intrigue, the struggle with inadequate equipment, and the ‘marauding corsairs from Bray and Wicklow’. The ultimate price was paid however, when the divers, Charles Spalding and his nephew Ebeneezer Watson died in their diving bell whilst

attempting to salvage the large treasure. Down on the wreck for the third time in their timber diving bell, at the Kish Bank off Dublin, they got into difficulties, and when the bell was raised, both men were found to be dead.

Spalding on Royal George (1782)

THIS DATABASE AND THE FUTURE

The shipwreck hunter who has journeyed through the time of hard-hat salvage and the development of SCUBA, will surely admit that developments have largely, but not entirely, rendered shipwreck research and hunting to the armchair.

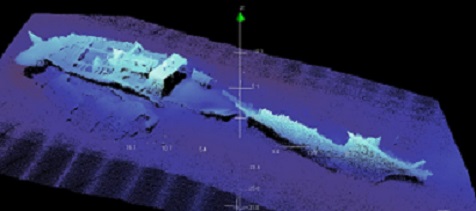

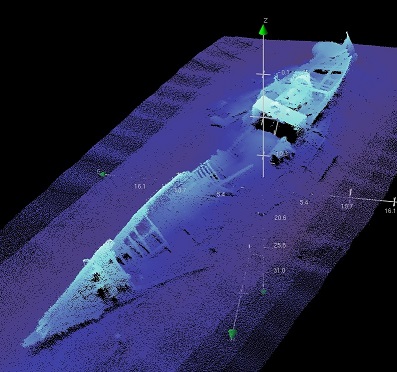

The ongoing detailed study of the Irish seabed by the Geological Survey Office of Ireland, in conjunction with The Marine Institute of Ireland – INFOMAR, are continuing to produce astounding images and a vast wealth of marine and geological data. This includes the discovery of many previously unknown shipwrecks. To their commendable credit, a great body of this work is available on line.

We exist during a time when maritime technology is conquering the deep at an expediential pace, and it is inevitable, that even more fascinating secrets of the deep will soon be revealed.

This database, more than 15,000 entries, consists of details, positions and images of numerous shipwrecks. It includes a large amount of diving information and images collected by the authors and diving companions. As a result of studies made of attacks by particular submarines against ships during WW1, some shipwrecks lost outside of Irish, but in UK waters, are also included.

Multibeam images of SS Hellenis (1869) by INFOMAR